A single administration of a specific treatment could potentially eradicate cancer.

Cancer-Zapping Injection Shows Promise in Early Trials

Brace yourself, cancer, 'cause a brand-new treatment is brewing, and it's targeting the Big C with pinpoint precision. Scientists at Stanford University have cooked up a clever combo of agents that stimulate the immune system, blasting away tumors in lab mice.

The world of cancer research has been burnin' hot over the last few years, as scientists tirelessly hunt for game-changing treatments. The latest addition to the chase involves high-tech nanotech, designer microbes, and even starvation tactics for those pesky malignant tumors.

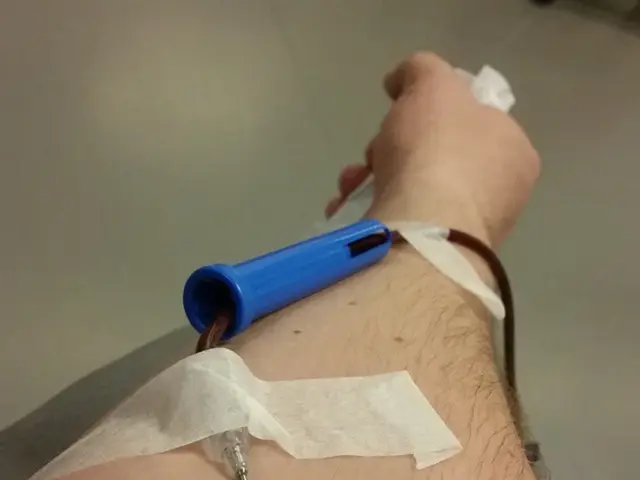

Now, Stanford University School of Medicine in California has taken a swing with a novel approach: a targeted injection directly into a malignant solid tumor. The key ingredients? Two agents that serve up a powerful immune system kickstart, all without the need for exhaustive immune system activation or costly customization.

Dr. Ronald Levy, senior study author and cancer-fighting guru, gives the lowdown: "With these two agents combined, we see tumors disappearing all over the mouse's body."

And get this - one of the agents involved has already received FDA approval for human therapy, while the other is currently under the microscope for treating lymphoma. So, the road to clinical trials for this star treatment could be a quick one, lotsa fingers crossed.

But how, you ask, does this immune system bootcamp actually work?

The One-Two Knockout Punch

Well, dear reader, Dr. Levy is all about immunotherapy, boosting the body's own immune response to take aim at cancer cells. There are varied methods of immunotherapy up his sleeve, but this new approach is quite the sneaky-sweet combo - a one-time, small-dosage application that turns immune cells into the tumor's worst enemies.

Here's the deal: when the agents are injected into the tumor, they activate the T cells, the immune system's white blood cells on steroids. Once activated, the T cells go on a rampage, finding and destroying not only the original tumor, but all the other malignant cells throughout the body.

[Notably, the scientists have reasons to believe that this approach could be adapted for various types of cancer.]

But how does the immune system normally know to wipe out cancer cells? For the most part, it doesn't. Many types of cancer cells have learned to outsmart the immune system by tricking T cells into thinking they're just part of the crowd.

But hold on, because in the new study, the team used two agents: CpG oligonucleotide, a synthetic DNA segment, and an antibody that binds to a certain receptor on T cells. Once T cells are activated, they venture out, seeking and destroying cancer cells elsewhere.

And the beauty of this approach is that immune cells aren't just learning to recognize one type of cancer - they're becoming expert cancer slayers, with the ability to zero in on and destroy multiple tumor types.

So, if the lymphoma treatment pans out, the team might just extend this treatment to even more types of cancer.

The Skinny on this Study

Now, it's important to point out that the experiments were only conducted on mice, but the results were downright killer. The team first tested this method on a mouse model for lymphoma, and a whopping 87 out of 90 mice were cured of cancer.

Similarly fantastic results were seen in mouse models for breast, colon, and skin cancer. And even mice that were genetically engineered to develop breast cancer spontaneously responded well to this treatment.

[Furthermore, the team found that the T cells only learn to recognize and attack the tumor in their immediate vicinity before the injection, but after that, they can migrate and wipe out other tumors.]

But what about cases where tumors of different types are present in the same animal? The team dug deep and discovered some treasure: they found that by injecting only the experimental formula into a lymphoma site, all the lymphoma tumors vanished, while tumors of a different type (in this case, colon cancer) did not respond.

[As Dr. Levy explains, "This is a very targeted approach...We're attacking specific targets without having to identify exactly what proteins the T cells are recognizing."]

Now, Dr. Levy's team is working hard to set up a clinical trial for people with low-grade lymphoma, with the hope that the study will pave the way for even more cancer types down the line.

Fingers crossed, cancer - your days are numbered.

[In addition to the study mentioned in the article, Stanford University School of Medicine has also been pursuing other innovative cancer treatments, including the TRACeR platform and the use of AI in cancer research.]

- The novel approach developed by Stanford University School of Medicine involves a targeted injection directly into a malignant solid tumor with two agents that stimulate the immune system, potentially eliminating tumors throughout the body.

- The agents in the injection activate T cells, White blood cells on steroids, turning them into the tumor's worst enemies, subsequently destroying not only the original tumor but also other malignant cells throughout the body.

- The beauty of this approach lies in the fact that immune cells aren't limited to recognizing a single type of cancer; instead, they become expert cancer slayers with the ability to zero in on and destroy multiple tumor types.

- The study's results showed promising outcomes, with a high cure rate in mice for various types of cancer, such as lymphoma, breast, colon, and skin cancer.

- The team discovered that they could target specific tumors without having to identify the exact proteins the T cells are recognizing, making it a highly targeted approach.

- The researchers at Stanford University School of Medicine are plans to set up a clinical trial for people with low-grade lymphoma, with expectations that this study could lead to further treatments for various cancer types in the future.