A single dose of treatment might potentially eradicate cancer cells.

A Wicked Turn in the Cancer Battle

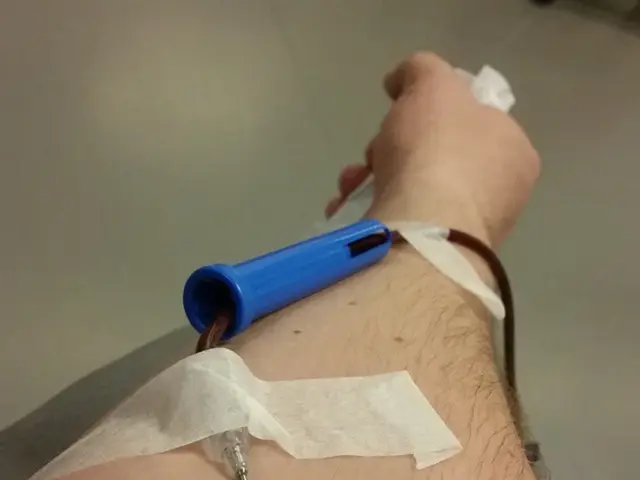

Scientists, ever on the hunt for a breakthrough against the vile scourge of cancer, have devised a cunning concoction - a targeted injection - that's already shown promise in obliterating tumors in rodents.

The race for a cancer remedy has been on a renaissance over the past few years, offering a glimmer of hope at every turn.

Experiments gallivanting on the cutting edge of technology include hunting down microscopic tumors using nanotechnology, using genetically engineered microbes to thwart cancer cells, and starving malignant growths to death.

The latest brainchild, from the ivy-covered halls of Stanford University School of Medicine in California, has delved into the possibility of another approach: injecting minuscule amounts of two agents that spark the body's defense mechanism directly into a malignant solid tumor.

This intriguing experiment, thus far, bears fruit in mice; "When we use these two agents together," explains senior researcher Dr. Ronald Levy, "we see the elimination of tumors all over the body."

"This method skips the need for pinpointing tumor-specific immune targets and bypasses the requirement for general immune system activation or personalization of a patient's immune cells," adds Dr. Levy.

Moreover, the researchers are optimistic about a quicker pathway to clinical trials for this method, as one of the agents involved has already received approval for human therapy, and the other is currently undergoing clinical trials for lymphoma treatment.

The study, published today in the journal Science Translational Medicine, details the researchers' exploration of a unique treatment method to fight cancer using immunotherapy. Dr. Ronald Levy, an expert in the utilization of immunotherapy to battle lymphoma or cancer of the lymphatic system, is at the helm of this endeavor.

This method, Dr. Levy suggests, is a game-changer, boasting benefits beyond its potential efficacy as a treatment. "Our approach employs a one-time application of negligible amounts of two agents to stimulate immune cells solely within the tumor itself," elaborates Dr. Levy. This technique enables the immune cells to learn how to combat a specific type of cancer, empowering them to migrate and demolish existing tumors in the body.

While the immune system plays an essential role in detecting and eliminating harmful external invaders, cancer cells of various types have learned to deceive the immune system, enabling them to flourish and spread.

T cells, a kind of white blood cell, play a vital role in regulating the immune response. Normally, T cells would zero in on and attack cancer cells, but all too often, cancer cells learn to swindle them and escape their destructive path.

The researchers' new strategy seems promising against a wide array of cancer types. In the new study, Dr. Levy and his colleagues applied this approach to mice with lymphoma, and 87 out of 90 mice experienced a cancer-free status. In the remaining three cases, the tumors returned but vanished following a second administration of the treatment.

Astonishingly similar results were observed in models representing breast, colon, and skin cancer, as well as mice genetically engineered to develop breast cancer spontaneously.

However, the scientists were quick to note that when they transplanted two different types of cancer tumors - lymphoma and colon cancer - in the same specimen but only injected the experimental formula into a lymphoma site, the effects on the colon cancer tumor were less evident. This indicates that the T cells only learn to address the cancer cells present in their adjacent vicinity before the injection.

As Dr. Levy explains, "This is a highly targeted approach. The tumor sharing the protein targets displayed at the treated site is the only one affected. We're attacking specific targets without having to know exactly which proteins the T cells are identifying."

Currently, the team is preparing a human trial to test the effectiveness of this treatment in individuals with low-grade lymphoma. Dr. Levy is optimistic that, if the trials are successful, they can extend this therapy to most types of cancer tumors in humans. "I don't believe there's a limit to the type of tumor we could potentially treat, as long as it's been infiltrated by the immune system," Dr. Levy concludes.

- This new treatment method, using immunotherapy, targets cancer by stimulating the body's defense mechanism directly into a malignant solid tumor, which has shown promise in eliminating tumors in mice.

- The study, published in the journal Science Translational Medicine, explores the possibility of using this treatment against other lymphomas and potentially various medical conditions like breast, colon, and skin cancer.

- The scientists are hopeful about the application of this treatment in medical-health-and-wellness, as one of the agents used has already received approval for human therapy, and the other is undergoing clinical trials for lymphoma treatment.

- If the human trials prove successful, the researchers aim to extend this therapy to most types of cancer tumors, believing that there is no limitation to the type of tumor they could potentially treat, as long as it has been infiltrated by the immune system.