Disturbances beneath the tranquil facade

Beneath the shimmering Kok River, a toxic threat slinks unseen. Arsenic, a harmful heavy metal, lurks in alarming levels, causing distress and uncertainty for the villagers who rely on it for their water, livelihoods, and health.

In the peaceful village of Ban Huai Kum, Supin Kamjai, 63, gazes at her withered vegetables with a hollow look. "We stopped using river water," she says, "but what good does that do now?" The rough hands that have tilled the soil for decades gesture towards the wilting greens - a harvest meant to feed her family for months.

Local community rights advocate Boonchai Phanasawangwong echoes her concern: "Our children play in the river, and now they have red, itchy rashes. No one is coming to check on us."

The crisis began in late 2024 when the once-clear water turned muddy. In Ban Kwae Wua Dam, children developed rashes after playing in the river. Downtstream, farmers in Huai Chomphu noticed their crops wilting despite daily watering. By early 2025, lab tests confirmed their worst fears: the river was contaminated with high levels of arsenic.

The contamination was particularly severe in Mae Ai district, Chiang Mai, where arsenic levels reached 0.026 of a milligramme per litre (mg/L) - well above the safety standard of 0.01 mg/L. Lead was also found at 0.076 mg/L, surpassing the safe limit of 0.05 mg/L.

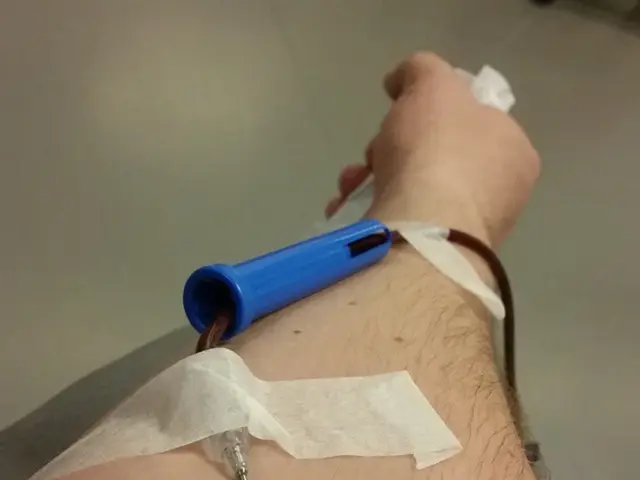

Health experts warn that arsenic, colorless, tasteless, and odorless, seeps silently into the body, potentially leading to skin lesions, organ damage, cancer, and developmental issues in children. The Environmental and Pollution Control Office in Chiang Mai has raised concerns about the potential risks if floodwaters cause contamination to affect local communities.

At the heart of the problem lies upstream mining activities in Myanmar's Shan State. Environmental groups and academic researchers suspect 23 gold mining sites operating without thorough environmental impact assessments (EIAs) as the source of the crisis.

Satellite imagery shows the presence of mining operations in the upper reaches of the river in the Shan State of Myanmar, potentially posing a risk of chemical contamination, as evidenced by the detection of arsenic and lead in the water flowing into Thailand.

The Thai government must assess whether the chemicals originate from neighboring mining operations and address the issue promptly to prevent a repeat of the 30-year lead contamination tragedy in Klity Creek, Kanchanaburi, which left generations of Karen villagers poisoned.

Mounting public pressure and scientific evidence have forced the Thai government to convene a high-level emergency meeting, bringing together key ministries to address the crisis. They have called for inter-agency coordination, data gathering regarding gold mines in Myanmar, temporary halts to mining operations, and improved mining practices.

For the families who have bathed in the river's waters and tended crops along its banks for generations, one plea remains: clean water and a path to restore the river's lifeblood. The Kok River still runs, but the fight to save it is only just beginning.

In the midst of their struggle, Supin Kamjai and Boonchai Phanasawangwong voice concerns about the impacts of medical-conditions linked to arsenic contamination on the health-and-wellness of their community, particularly children. As environmental-science experts warn about the danger of climate-change, they urge the Thai government to address the crisis, conduct thoroughly studies on gold mining sites upstream in Myanmar's Shan State, and implement stricter mining practices to prevent further environmental damage and ensure the safety of the Kok River's water.