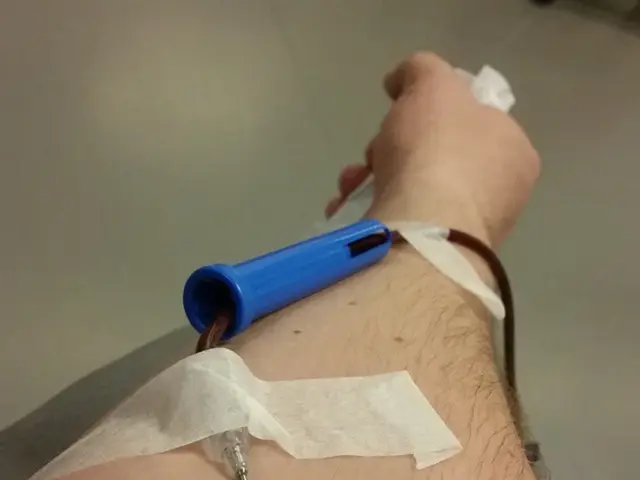

Human participants to undergo transfusions of artificially produced 'synthetic blood' in a laboratory setting.

In the realm of medical innovation, the development of lab-grown blood is a promising breakthrough that could significantly transform the way we approach blood transfusions and global health infrastructure.

Current research, led by teams such as Professor Antal Rot's at Queen Mary University of London, focuses on using stem cells, specifically hematopoietic stem cells, to generate red blood cells (RBCs) in the laboratory. The process involves nuclear expulsion in around 80% of stem cells, but the limited sources like umbilical cord blood or bone marrow make large-scale production challenging. Progress is being made in reprogramming other cell types into pluripotent stem cells to create an unlimited cell source, although this method is slower and currently less efficient.

In parallel, Japanese researchers, led by Professor Hiromi Sakai at Nara Medical University, have developed NMU-HbV—a synthetic, hemoglobin-based oxygen carrier designed to mimic the oxygen transport function of natural RBCs. These artificial RBCs are stable at room temperature for years, do not require blood type matching, and eliminate nearly all infection risks since they lack cellular components that can carry viruses or provoke immune reactions. They are produced using hemoglobin extracted from expired donated blood, encapsulating it in lipid vesicles for safe circulation.

Both approaches are still in clinical trials, with synthetic substitutes potentially ready for real-world use by the end of the decade, while stem cell-derived blood faces longer timelines due to complex manufacturing challenges.

If successful, lab-grown blood could address the issue of rare blood types, which are often in critically short supply for patients with uncommon antigen profiles. It could also provide a solution for patients with chronic disorders requiring regular transfusions, such as sickle cell anemia or thalassemia, by reducing dependence on donors and the risk of iron overload from repeated transfusions.

The synthetic hemoglobin-based products are nearly free of infection risk, making them invaluable in emergency and trauma situations, especially where screening time is limited or sterile conditions are difficult to maintain. They could also revolutionize global health infrastructure, providing aid in battlefield medicine, space exploration, disaster zones, and more.

However, both technologies face challenges. Scaling up production remains a major hurdle for stem cell-derived blood, while synthetic substitutes lack the full range of blood functions, limiting their use to acute oxygen delivery rather than comprehensive blood replacement. Both technologies are still in clinical trials, with safety, efficacy, and long-term outcomes yet to be fully established.

In conclusion, lab-grown synthetic blood holds transformative potential for addressing shortages of rare blood types, reducing infection risks, and revolutionizing emergency medicine—especially in resource-limited settings. However, current methods each have significant limitations, and widespread clinical impact will depend on overcoming these technological and regulatory challenges in the coming years.

In the world of health and wellness, advancements in technology and science, such as the development of lab-grown blood, could revolutionize therapies and treatments for medical conditions like rare blood types and chronic disorders that require frequent transfusions. For instance, stem cell-derived blood holds promise in addressing shortages of rare blood types, while synthetic blood substitutes may offer significant advantages in emergency and resource-limited situations due to their stability and reduction of infection risks. However, both technologies face challenges in terms of scaling up production and fully replicating the functions of natural blood, making it crucial for researchers to continuously innovate and address these hurdles to ensure the successful integration of these groundbreaking technologies into health infrastructure.